The Use of Thermography in Lameness Evaluation

by Tracy A. Turner, DVM, MS, DiplACVS

Lameness diagnosis can be very frustrating when the source of pain is located in the upper leg and is not associated with a synovial structure, if the lameness is too subtle to utilize diagnostic analgesic injections, if the patient is not amenable to these injections, or if the lameness is difficult to eliminate by local analgesic injection. These cases usually require the practitioner to treat the horse symptomatically or to perform other diagnostic techniques to try determining possible areas of injury.

Thermography is one such technique. It is the pictorial representation of the surface temperature of an object. It is a non-invasive technique that measures emitted heat. A medical thermogram represents the surface temperatures of skin, making thermography useful for the detection of inflammation. Although thermographic images measure only skin temperature, they also reflect alterations in circulation of deeper tissues. This ability to non-invasively assess inflammatory change makes thermography an ideal imaging tool to aid in the diagnosis of certain lameness conditions in the horse. The purpose of this article is to describe the use of thermography as an aid to clinical lameness diagnosis.

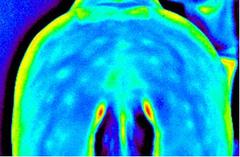

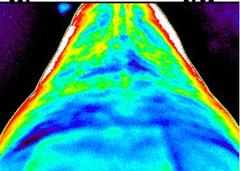

Thermography has most commonly been used to evaluate horses with back or hind limb lameness. The second most common use of thermography was to evaluate the horse for performance or pre-purchase. In this capacity, the horses were examined to determine if any area of inflammation could be detected that would account for decreased performance, to determine a source of pain that might explain a horse’s change in attitude toward work, or to try to identify subclinical areas of inflammation. Thermography has been used least frequently for investigation of forelimb problems. Thermography has provided significant information in 86% of the horses examined. Temperature changes were identified as either “hot spots” (Note- Green/ Yellow on top of the back)

or “cold spots.” (Note: Blue spot in the middle of the back)

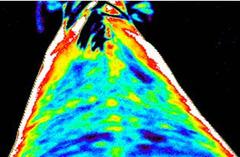

The thermographic image was very useful in localizing the area of injury, but did not characterize the specific nature or etiology of the injury. Investigation of the upper limb lameness was the region where thermography was most useful. The most frequent upper limb problems were located over large muscle masses and thought to be either muscle strains or muscle inflammation. In the upper foreleg, the most common areas of temperature asymmetry were located over the pectoral muscles or the biceps brachii (shoulders). In those cases showing increased heat over the shoulder region, we were able to identify specific lesions within the biceps tendon or bicipital bursa utilizing ultrasonography.

In the upper hind leg, abnormal thermal patterns of three distinct regions were commonly seen: cranial thigh, caudal thigh, and croup region. In the cranial thigh, distinct hot spots were associated with the quadriceps musculature just proximal to the insertion on the patella. In each of these cases, we have been able to subsequently find evidence of muscle damage utilizing ultrasonography. The caudal thigh thermography showed several common areas of abnormal heat. The most common was at the musculo-tendinous junction of the semitendinosus muscle. A third area of abnormal thermal patterns was commonly seen in the caudal thigh, just caudal to the third trochanter of the femur directly over the biceps femoris. The thermal changes noted were both a “hot spot” and an intense “cold spot.” We have not correlated any sonographic findings with this injury to date. The croup area injuries involved hot spots over the loin region, over the sacroiliac region, over the body of the gluteal muscle, and over the third trochanter. Ultrasonography has been used in these cases to characterize a “muscle cramp,” dorsal spinous ligament desmitis, and suspect sacroiliac desmitis. Fasciitis was diagnosed in one case based on muscle biopsy. In the assessment of horses that “tie-up,” thermography indicated that the longissimus and gluteal muscle regions had the most intense heat. Further, the behavior the horse showed during the “tying-up” episode correlated with the thermal patterns. Horses that became stiff showed the most intense heat over the longissimus muscles, whereas horses that would stop and be very reluctant to move showed the most intense heat over the gluteal region.

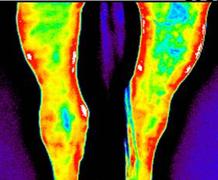

New, more portable thermographic equipment is now available. Because of this we have used thermography more frequently in the evaluation of various forelimb lamenesses and exercise-related problems. Thermography is being used in the evaluation of forelimb lameness to assess the intensity of inflammation as well as to gain insight into the stresses or inflammatory nature of various types of lameness. In addition, we can evaluate various problems at the barn under the conditions where the horse actually shows the problem. This has allowed several tack-related problems to be identified by the thermal patterns caused by the tack while the horse is being ridden. It has been our experience that thermography specifically increases the accuracy of diagnosis by confirming inflammation in palpably sore areas and by providing objective data that indicates in which area to concentrate further diagnostic testing such as sonography, radiography or muscle biopsy.

Heat is one of the cardinal signs of inflammation and is associated with a thermographic “hot spot.” “Cold spots,” however, may also be a sign of injury and reflects the presence of marked swelling or results from decreased circulation in the damaged tissue or of the presence of dense scar tissue. Thermography, when combined with a thorough clinical examination by your veterinarian, is an excellent imaging technique to assess lameness. It is particularly helpful in determining areas of inflammation in the upper limbs, but can also be readily used to assess inflammation of the lower limbs. It has been useful in assessing cases of palmar foot pain and has helped to identify areas other than the navicular bone that may be sources of pain. It has been useful in the assessment of joint problems as well as tendon and ligament problems. Since the modality is non-invasive, it can readily be used and, with recent technological advances, the equipment is completely portable and can readily be taken into the field.

(Note: Left side of picture, inside of the leg (RED))

(Note: Abnormal Back Pattern)

You must be logged in to post a comment.